New Zealand’s greatest health threat is not sudden or spectacular. It does not arrive in waves like a pandemic or dominate headlines for weeks at a time. Instead, it creeps forward quietly, year after year, filling clinics, wards, and waiting rooms. Chronic, non-communicable diseases are now the dominant cause of health loss in Aotearoa — and we are still treating them as background noise rather than the central challenge they are.

Cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic respiratory conditions account for a vast share of illness, disability, and premature death. These are not rare or exotic diagnoses; they are everyday realities for hundreds of thousands of New Zealanders. They drive the majority of GP visits, hospital admissions, medication use, and long-term care needs. Yet our health system remains oriented toward episodic, reactive care, rather than sustained prevention and early intervention.

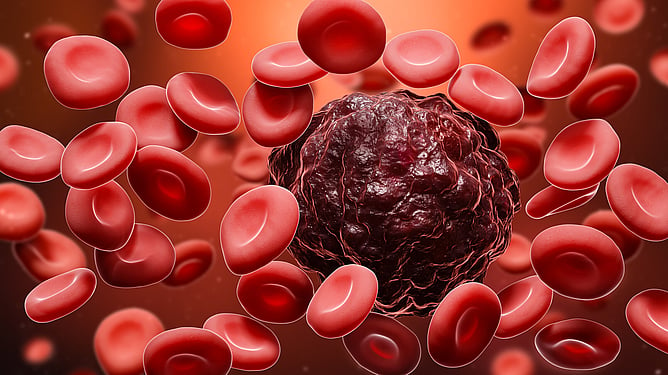

Cancer illustrates the scale of the problem starkly. It is now the leading cause of death in New Zealand, with lung, breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers the most common. While advances in treatment have saved lives, too many people are still diagnosed late, when disease is harder to treat and outcomes are poorer. Screening coverage remains uneven, access varies by postcode and income, and prevention efforts struggle to compete with the social and commercial forces driving risk.

Underlying many of these conditions is a shared set of drivers — obesity and high body mass index chief among them. Excess weight is not simply a lifestyle issue or a matter of personal choice; it is shaped by food environments, housing quality, transport systems, income insecurity, and time poverty. When cheap, calorie-dense food is abundant and safe spaces for physical activity are scarce, “individual responsibility” becomes an inadequate explanation and an even poorer solution.

The burden of chronic disease is not evenly distributed. Māori and Pacific peoples experience higher rates of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and some cancers, often at younger ages and with worse outcomes. These inequities reflect long-standing structural factors, including access barriers, racism within the system, and the cumulative effects of deprivation. Addressing chronic disease without addressing equity is not just ineffective — it is unjust.

The economic consequences are equally sobering. Long-term conditions drive ongoing healthcare costs, reduce workforce participation, and increase demand for disability and social support. Every preventable heart attack, stroke, or late-stage cancer diagnosis represents not only personal loss, but a failure of collective policy and planning.

If New Zealand is serious about improving health outcomes, chronic disease must move from the margins to the centre of decision-making. That means investing upstream — in prevention, early detection, culturally grounded care, and environments that make healthy choices realistic rather than aspirational. It means measuring success not by how many procedures we perform, but by how much illness we prevent.

The slow-burn crises are often the hardest to confront. But they are also the ones that define our future. Chronic disease is already shaping New Zealand’s health system. The question is whether we will finally choose to shape it in return.

The slow-burn crisis of chronic disease cannot be solved by the health system alone. At Levin Family Health, we spend much of our time managing the consequences of these conditions — heart disease, diabetes, respiratory illness, and cancer — often at advanced stages. Clinicians work hard every day to stabilise, treat, and prevent deterioration, but meaningful progress depends on partnership. Long-term conditions do not improve through one-off appointments or short bursts of care; they require sustained engagement, trust, and shared commitment over time.

That is why patient and whānau buy-in matters. We are here to help people improve, recover where possible, and live well with ongoing illness — but this only works when care is seen as a joint process rather than something delivered passively. Lifestyle change, medication adherence, monitoring, and early presentation are not add-ons; they are central to better outcomes. Without that shared understanding, the system is left responding to crises rather than preventing them.

Our long-term conditions team views this work as one of the most important parts of primary care. Their role is not just to manage numbers or tick boxes, but to support people through the realities of living with chronic illness — adjusting treatment early, identifying risk sooner, and reducing the need for hospital care later. In a system under pressure, this kind of proactive, relationship-based care is not a luxury; it is essential.